I have been thinking about simple house forms and their straightforward geometry.

I was asked about window placement for a modern saltbox. I had no simple

answer. A traditional saltbox has a door

in the middle and a room on each side. The windows are evenly spaced because

vernacular construction in the western world was evolving from medieval to renaissance design. A modern saltbox? Is it an oxymoron and if not, what would be right? That's the background. Below is the geometry for a vernacular saltbox.

Settlers in the Colonies included a good number of carpenters; men who had finished at least their 7 year apprenticeships. Still every family needed a house, so a straightforward plan was required; one that was easily laid out with available tools, like twine and chalk or charcoal - a Line. A carpenter square was useful, but not always truly square; it needed to be checked by geometry.

The form that developed was a simple vernacular American house - 2 rooms over 2 rooms with a center entrance. Common all over the Eastern Seaboard, it went west with the settlers. The lean-to - its sloping roof the signature of a saltbox - was regularly added to the back, first for storage, later to expand the house.

My diagrams here are for a simple generic New England saltbox.

The carpenter needed to decide how wide, how big the rooms would be. He choose the same length for the depth and width of the parlor and the hall. That first length governed all the choices, the placement, the patterns, the dimensions that followed.

The carpenter needed to decide how wide, how big the rooms would be. He choose the same length for the depth and width of the parlor and the hall. That first length governed all the choices, the placement, the patterns, the dimensions that followed.

He knew the fireplaces and chimney stack would be placed in the middle so he made space for them. Then he laid out a square on one side, and another on the opposite side. This became the guide for his timber frame.

Here is the sequence that begins with a length and ends with a square. A carpenter knew practical geometry. He knew how to use a straightedge and a Line. He had no ruler or tape measure. He probably began with the 5th diagram. He didn't need a physical compass. His Line could be pinned at one end and then swung in an arc to mark the corners. The resulting square could be checked (trued) by matching its diagonals.

My mythic carpenter choose a room depth of 16 feet. 20 feet was a common length in later houses. The diagram is to scale; it is 16 ft. deep and 40ft. wide. I have allowed 8 ft. for the fireplaces and chimney.

The same square - 16 ft. x16 ft. - was used for the height. Here it is divided in half for the first and second floors.

The ridge of the roof frame is half the height of the box - 8 feet.

Sometimes the dimensions for the framing began at the foundation. Sometimes the dimensions began after the sill was laid, made level and true.

Here are the posts, the beams (called girts), and the rafters laid out. Next will come the summer beam, and then the joists.

For reference I am using Abbott Lowell Cummings' framing from his booklet, Architecture in Early New England. His first diagram is entitled "Typical framing details.." . The second, "seventeenth century house plan" shows the early fireplace and chimney configurations. (see below)

The windows were centered in the shape, right in the middle. Glass was a luxury in early houses; windows were small.

There might not have been one in the attic.

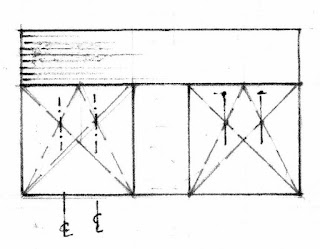

Here is the diagram for easily finding the center line of the square. Swing the arc of the length as shown in the first square -dashed red lines, solid black lines. The crossing points are centered on the square as shown with the solid and dashed lines in the second square,

The front elevation of the house was as simple as the floor plan and the side elevation: 2 squares with the chimney stack in the middle which also gave room for a stair and a entry door.

I've added shading to the roof.

The layout shows the post and beam frame, ready for the summer beam and the floor joists. All of this could be laid out with Lines, made true and square by the diagonals, which are also Lines. A Line might be chalked to leave a mark ( a Line) on a framing floor, or it was a length of twine pinned in place by an awl, or tied to a stake.

Here's the front elevation with one window centered in each room.

As glass became more available more windows were added.

There were 2 ways to place the windows using the geometry of the Rule of Thirds. Here on the left the square is divided into thirds, the windows centered on that Line.

On the right the inside edges of the windows are on the Line.

Here is a diagram for the Rule of Thirds. The diagonals for the square are crossed by the center line. Then new diagonals - red - are added to the rectangles on either side of the center line. The diagonals of the square cross the diagonals of the rectangles at points which divide the square into thirds.

I have only shown the square's diagonals and the red diagonals in the drawing which shows window placement. The square with all its Lines can be visually overwhelming.

This diagram shows the squares divided into thirds - the dashed lines. On the left the windows are placed on the center line - dot-dash lines. On the right the inside edge of the window is on the Line - solid lines.

In a new community settlers from different areas brought different framing traditions. 2 houses side by side might use different patterns, reflecting the carpenter's background.

The lean-to was an obvious expansion: just an extended roof covering the new space. The space did not always include a fireplace. When a fireplace was added it was laid up against the existing masonry.

The lean-to was an obvious expansion: just an extended roof covering the new space. The space did not always include a fireplace. When a fireplace was added it was laid up against the existing masonry.

Here is the diagram showing the carpenter's Lines.

Note that while in a diagram the roof would meet an 8 ft deep and 8 ft high room at the upper far corner, in reality the width of the posts and beams and rafters often made for a lesser height.

The back wing was useful. It often was 10 feet deep. The diagram shows how the roof pitch changed. If the lean-to were added after the main house was built, the rafters might join the frame under the roof. That would also lower the roof pitch.

Here is the window placement; all are centered on their interior spaces.

The photograph at the beginning of this post shows how owners adapted and updated the basic house. More windows were added on the sides. The front windows were sometimes enlarged. Columns and an architrave with molding were added to the front door. After 1780 front entries were added to many houses.

The rhythm. pattern, proportions - the geometry, including the window sizes, of a Georgian saltbox came from its construction, the available materials, and its function. It used timbers and hand tools to create shelter. It did not need to accommodate bathrooms or closets, nor provide much privacy. I think a modern saltbox, built with modern materials and tools for 21st Century life, will need its own rhythms, patterns, and proportions.

This is Abbott Lowell Cummings' first illustration in his pamphlet, showing the frame I have laid out - a center chimney with a room on each side on each floor.

The main floor plan shows how the lean-to was added and used. This plan, common on the New England seacoast, came with settlers to western Massachusetts,Vermont, and upstate New York. It is often inside what appear on the outside to be Federal and Greek Revival houses. The chimneys move, the ceiling are taller, the stairs more gracious, but the floor plan remains.

Abbott Lowell Cummings' plan is not as 'square' as my diagrams. Here is the geometry. The Hall on the right is a square room. The dashed red arc is the width of the room transferred to the length.

The width of the Parlor matches the Hall, but its length is shorter. It is determined by where the arcs of the width, the red dashed lines, begun at each corner of the fireplace, cross.

The layout for the house, its rooms, begins at the chimney stack. It seems to have been placed first, the house framing against and around it.

The back wing is set true with the house using the 3/4/5 triangle which will always have a square corner, red dotted lines. Here the wing is square, 'true', with the existing house.

* Abbott Lowell Cummings, Architecture in Early New England, Old Sturbridge Village Booklet Series, Sturbridge, MA, printed by the Meriden Gravure Company, Meriden, CT. 1974.

In this post I have capitalized Line because those who wrote pattern

books capitalized it, and because the Line creates the design.

The name 'saltbox' was given to these houses in the late 1800's, by New

Englanders who had salt boxes of a similar shape in their kitchens. In

the southern US, these roofs were/are referred to as 'cat slides'. The

saltbox houses whose geometry I have studied have wonderful variations and quirks. Often these are due to the changes in fireplace, bake oven, smoke chamber, flue, and chimney construction technology.

The photograph of the Kimball House comes from the archives of the Andover Center for History and Culture.