A short history of classical pediments in the Western world, c. 1540 to c.1903.

Vignola's Rule was first laid out by Giacomo (Jacopo) Barozzi da Vignola in his Cannon, published in 1562.

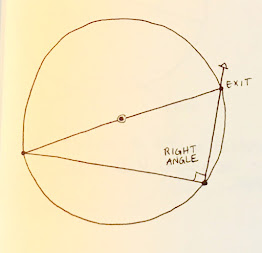

This image was published in 1903 in William Ware's The American Vignola.*

Was it Vignola's rule or did he just record it?

It's possible that the Rule itself was already widely known.

He wrote, "...

having drawn the cornice, divide the upper line from one side to the other in the middle, between A and B; drop half of this plumb from the middle to make C; then placing one compass point on C and the other on the side of the cornice A, arc to the side B; the highest point of the curved line will mark the required height for the pediment. A curved pediment can also be made with such a rule."*

The diagram shows the actual twine held tight at Points A and B. It is a Line with its ends dangling and curling.

Palladio doesn't describe this, but the roofs in his The Four Books of Architecture (1570) use the same pitch.

Vignola's book on architecture was translated, of course.

This image, c. 1600, attributed to Vignola, comes from a book published in Spain.

His 5 Orders of Architecture* were translated into English and published by John Leeke in 1669. Vignola's portrait (Plate I) is surrounded by a decorative frame topped by an extravagant pediment. It does not quite follow Vignola's Rule. Follow the red lines.

John Leeke' book included 3 pediments attributed to 'Michel Angelo'. This one, the simplest, does seem to use Vignola's formula. The angle is the proper 22.5*. Did Michael Angelo know of Vignola's work?

A complete English translation of Serlio's 5 Books on Architecture, including the sketch of the pediment's layout, was available in the UK about 1720.

James Gibbs probably had read both Vignola and Serlio. He uses the geometry in the pediment of a Menagery, in his book, On Architecture*. Perhaps Gibbs includes the knowledge of this diagram when he writes that his 'draughts ... may be executed by any Workman who understands Lines'.

William Salmon's book, Palladio Londinensis*, published in the 1750's, was intended for the London builder. Pediments are included; their proportions are measured in parts. Perhaps Salmon considered the understanding of geometry by London's builders to be scant, or that it was not applicable to London's tightly set row houses.

The rule for laying out a pediment came to the States with craftsmen as well with their pattern books. The Rockingham Meetinghouse, finished by 1797, is a classic New England meeting house: plain and unadorned...

until you look at its doors. The pediments of the classical frontispieces follow Serlio's layout.

I began my diagram here on the lower edge of the pediment's frame. If the layout is moved to the upper edge of that plate, the arc marks the top of the ridge of the pediment roof, rather than at the underside.

At about the same time William Pain includes the same arcs (lightly dashed here) and describes how to draw them in The Practical House Carpenter,* a pattern book widely available in the States.

Here is Asher Benjamin's simplification of Pain's engraving in The Country Builder's Assistant*, published in 1797.

This door front in Springfield, VT, c. 1800, was probably inspired by Benjamin's illustration.

The Industrial Revolution brought new tools and materials. Galvanized metal allowed shallow roof pitches which didn't leak.

Here's an example of a shallow roof pitch from Samuel Sloan's pattern book, The Modern Architect*, published in 1852 .

Sloan's Plate XXXV shows the steeple structure. The frame spanning the building uses the traditional roof pitch of Serlio's pediment (22*). The pitch of the roof is much shallower (15*)

For the next 50 years architectural style was giddy with the designs made possible by the Industrial Revolution.

By

1900, the design possibilities made possible by 60 years of

industrialization were taken for granted. Architects looked to Europe, especially the Ecole des Beaux-Arts in Paris, for inspiration, and perhaps a re-grounding in tradition.

William Ware wrote The American Vignola in 1903 as a guide for his students at the Architectural School of Columbia University.

Here's his Plate XVII with many pediments. The dotted lines compare measured/built pediments in Greece and Rome to Vignola's standard.

The 2 small diagrams on the right side Plate XVII are his codification to Vignola's Rule.

As I compiled these illustrations I found 2 caveats:

Owen Biddle* published his pattern book in 1804. Instead of a general rule for 'a pitch pediment frontispieces', Biddle wrote that the roof angle was 2/9 of the span. He also wrote that for 'the townhouse with a narrow front... the true proportions of the Orders may be dispensed with..." p. 34

William Ware noted that "...if a building is high and narrow, the slope needs to be steeper, and if it is low and wide, flatter." p. 45

And finally, this advice from William Salmon: "...when you begin to draw the Lines,... omit drawing them in Ink, and only draw them with the Point of the Compasses, or Pencil, that they may not be discovered when your Draught is finished..." p. 103.

*The books from which I have copied illustrations and quotes for this blog are listed in alphabetical order by author.

Asher Benjamin, The Country Builder's Assistant, Greenfield, MA., 1797, Plate 10.

Owen Biddle, The Young Carpenter's Assistant, Philadelphia, 1805, Plate 15.

James Gibbs, On Architecture, London, 1728, introduction and Plate 84.

William Pain,The Practical House Carpenter, fifth edition, London, 1794, Plate 38.

Sebastiano Serlio, On Architecture, , c. 1545, Book IV, page xxviii.

Samuel Sloan, The Modern Architect, 1852, Plates XXVII and XXXV.

WilliamWare, The American Vignola, W.W. Norton & Co., NYC, 1903, Plate XVII.

.jpg)

.jpg)

.jpg)

.jpg)

.jpg)

.jpg)