A note on Owen Biddle's Plate I, Diagram G. in his pattern book for beginning carpenters. *

I wrote about Diagram G on this post: https://www.jgrarchitect.com/2020/06/practical-geometry-lessons-lesson-5.html

I said that Biddle was not just introducing his 'carpenter assistant' to geometry; in Diagram G Biddle was explaining how to layout a square corner to work out a structural detail, cut a board, or set a frame on site.

Since then I have explored the theoretical geometry of that diagram.

The number of right angles which can be drawn in a circle is infinite. The rule always works. That understanding is part of why geometry is seen as mystical or sacred.

This 'squaring the circle' diagram is from

Robert Lawlor's Sacred Geometry*. (page 77, diagram 7.5)

It uses a geometry similar geometry to Biddle's diagram G: a diameter and an angle. Here the diameters are evenly spaced and the same angle is used at every point on the circumference. But the angle is not 90*. It is not a 'square angle'.

This is decorative, not structural.

The shapes do not close. The line continues for 5 rotations. It does not create a square, but seeks to define the perimeter of a circle with straight lines.

,

I am often told that I work with Sacred Geometry, that the geometric patterns I recover are theoretical,

mystical, and sacred. I agree they are geometry. No, they are not sacred. They are practical. They are geometry used in construction.

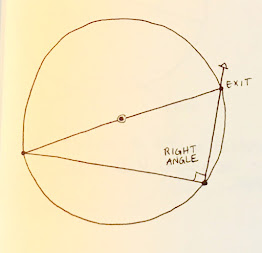

Here is how Biddle's diagram comes about:

Begin with a point - A

Choose a radius - A-B, and draw a circle. Using the daisy wheel find the diameter - B- A- C, dotted and dashed line.

Pick a point on the circumference of the circle - D.

Here I have chosen 3 different D's at random.

Connect B-D and D-C.

Each diagram will have a 90* (right) angle at the intersection of B-D-C.

Wherever the D is placed. the angle will be 90*.

Biddle's Diagram G begins with my line B-D.

It describes how to find my 90* angle of B-D-C. (his a-b-c) The answer is to find the diameter of a circle (a-d-c) that intersects a. That will give c. That will give the 90* the carpenter needs.

By Hound and Eye* has a very similar diagram for drawing a right angle .

The book is a guide to furniture design, full of practical geometry. Each geometric problem is described step by step; practice work sheets are included.

This pattern is the beginning of a handmade try square.

*Owen Biddle's The Young Carpenter's Assistant, 1805, Philadelphia. Dover Publishing reprint, See my Bibliography for more information.

*Robert Lawlor, Sacred Geometry, Philosophy and Practice, 1982, Thames and Hudson, London.

*Geo.R. Walker & Jim Tolpin, By Hound and Eye, A Plain & Easy Guide to Designing Furniture with No Further Trouble, 2013, Lost Art Press, Kentucky The diagram shown above is from page 57.

This pattern is 4 overlapping hexagons.

My granddaughter, who is 7, watched me add the images to this post.

She

wanted us to 'square the circle'. I did, using right angles where the

diameters met the circumference. That produced these overlapping 6 hexagons, not

squares.

She watched closely and observed that accurate work was not easy: my lines did not always cross exactly in the center of the circle. When we finished she asked me to erase all the diameters. This is the result. Maybe she will show me later what she added to the copy I printed for her.