For Laurie Smith, my friend

Here are the front and back covers of Laurie Smith's last book.

The book is full of beautiful photographs of medieval framing and the

history of the conception and construction of these barns' frames -

from felling the trees to placing the aisle braces.

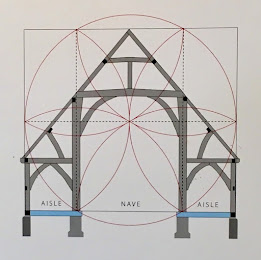

Of course, as the book is about Geometrical Design, it's also is full of

daisy wheels and explanations of how they were used to design the

Harmondsworth Great Barn.

Laurie Smith was a Geometer, probably the

best. He researched, wrote, and taught architectural (aka 'practical')

geometry. His language and his drawings are clear and engaging.

It is a book to read, think about, study. It can be read by a novice as well as one well versed in geometric construction. Laurie's first Drawing 1 is titled: "Names and Locations of the Frame's Timbers". It's accompanied by a Chart: "Heavy timbers needed for the barn's section". From that basic introduction he explains the geometry of the barn.

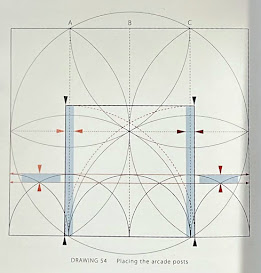

If at Photograph 39 you aren't sure what an 'arcade post' is, that first drawing is readily available. Using Photograph 39 Laurie explains how - with simple drawings, photographs, and the language of timber framing - arcade posts, arcade plate jowls and buttresses fit together and why they are important.

Then you understand Drawing 54.

Laurie doesn't just quote Vitruvius. He spends time with those terse sentences in Book I, De Architectura, exploring as a Geometer, whose tools are a compass and rule, what Vitruvius means when he writes a "...plan is made by the proper successive use of compasses and rule".

Laurie includes a carpenter's dividers, probably his own. He explains how they are 16.5 inches long, proportional to a rod which is 16.5 ft., and discusses 'stepping off'.

The geometric analysis of other great barns - The Barley Barn, Cressing Temple, Essex, and the Leigh Court Barn, Leigh, Worcestershire - is thorough and clear.

The Notes and Credits are good reading, not a perfunctory listing of people and books. There is much here to absorb, come back to, consider again.

Laurie finished the text, the geometric drawings, and the

design in the summer of 2021. It was published that fall by Historic Building

Carpentry in partnership with the UK Carpenters' Fellowship.*

He sent me a copy. I read it twice and told him how much I liked it. At his request I sent copies to a few of the timber framers in the States who had worked with him .

I wrote that I'd put a review on my blog as I had before for his book on a barn in Devon. Here's the cover of that book.My review is: https://www.jgrarchitect.com/2020/11/architectural-geometry-rare-geometrical.html

We

enjoyed seeing that over 700 people had read that review. (now over 800)

We wondered how many had found his website through my blog post.

He listed my blog on his website. I hadn't yet figured out how to list his on mine.

We talked about the geometry we'd explored and learned about in the last 8 years.

Then Laurie died, December 2, 2021.

Now it's hard to read his books. I want to send an email across The Pond , "Yes, and what about....?"

Then I remember that I read Durer, Serlio, Palladio and feel that they are speaking to me directly, 500+ years later. Like them, Laurie's spirit is in his book. His words share his awe, his joy, and profound understanding of the geometry he saw, knew so well, and loved.

*The Geometrical Design of the Harmondsworth Great Barn is available through the Carpenters' Fellowship, ( https://carpentersfellowship.co.uk/) in the UK. I act as the distributor in the States. Please contact me if you would like a copy @ $25., including postage.